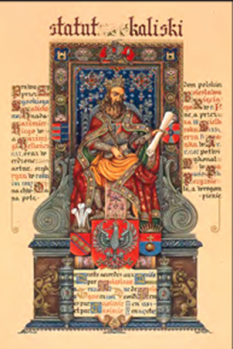

We, Boleslaw, by the grace of God the Duke of Wielkopolska, hereby make it known to both those of the present and of the future, to whose notice the present write shall come, that to our Jews living all across the lands of our Dominion, We have resolved to declare word-for-word the statutes and privileges that they have obtained from us.

The Statute of Kalisz, 9 September 1264

The Ashkenazi

Though we don’t know exactly when our ancestors came into Europe, it is very likely that it happened prior to 1000 CE. Starting in the 1st century CE, accompanying Roman Legions, Jews began entering what is the modern borders of France and Germany. Over the next several centuries the Jewish population grew in western Europe as Jewish merchants followed trade routes north from Byzantium. These new arrivals into Germany and France brought with them ancient Palestinian and Babylonian lore, laws and especially their patterns of Jewish living (minhagim).[i]

These communities flourished when, in 814 CE, Charlemagne became the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He, and later his son, Louis the Pios, issued charters granting them protection, exemption from tolls, guarantees of religious practice and the right to use their own Rabbinical Court. As Catholics were prohibited from charging interest, Charlemagne and later kings encouraged further immigration to allow Jews to become their bankers and international merchants. By 900 CE, the largest Jewish population in Europe was in Mainz, Germany. In Mainz, Jewish communities were self-contained with legal decisions rendered by religious judges and Rabbis. Communal control was led by town elders. The result of this self-rule was the powerful feeling of loyalty to the traditions of their forebearers, “Minhag avoteinu”. As a result, a strong European Jewish culture began to form. In 1100 CE it was first named Ashkenazi.[ii]

In 1096 CE, Western Europe’s attitude towards its Jewish citizens took a dramatic turn. It started when, Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, united with Pope Urban II, who preached a crusade against the Islamic world and the capture of the Holy Land. Over 40,000 men and women were gathered into a paupers’ army. Before going to the Holy Land, they set their sights closer to home, targeting German Jews. The Solomon bar Samson Chronicle quoted an anonymous source as saying:

Look now, we are going a long way to seek out the profane shrine and to avenge ourselves on the Ishmaelites, when here in our very midst, are the Jews – they whose forefathers murdered and crucified him for no reason. Let us avenge ourselves on them from among our nations so that the name of Israel will no longer be remembered. [iii]

These crusaders cut a bloody path through Europe, despite appeals from many bishops and Henry IV, the Holy roman Emperor to cease this slaughter.[iv] The devastation of the crusades was captured in piyyutim (Jewish liturgical poetry). These poems related the Jewish suffering at the hands of the crusaders, with the destruction and martyrdom of ancient Jerusalem. This instilled a new Ashkenazi tradition of remembering the dead on the Day of Atonement. Over time this would expand to Sukkot, Passover and Shavuot.[v]

Also in 1096, Gershom ben Judah became a major figure in establishing the role of women in the Ashkenazi communities. He created ordinances, in Mainz, banning polygamy. This ordinance also required a Jewish wife’s consent for a divorce. This practice quickly spread throughout France, England and the German empire. Over time, women’s role in providing economic support for their family expanded.[vi]

Over the next 4 years, domestic crusades continued. This resulted in the first extensive Jewish migration from Western Europe into Poland. Attracted by the tolerance shown by Duke Boleslaw III (1102-1139),[vii] it is possible that some of our ~36th great-grandparents arrived in Poland or a nearby country. If so, their descendants would live in Poland for the next 8 centuries.[viii]

Further migrations would take place. In 1230, Jewish lending was made illegal by Louis IX, he later confiscated all Jewish loans, and in 1248-1249 expelled all Jewish lenders. Around this same time, in Vienna, Jews were forced to wear a cone shaped hat and a yellow badge (providing inspiration for future atrocities). Things were just as bad in England when in 1290, King Edward expelled over two thousand of his Jewish citizens.[ix]

1298 CE represented the beginning of a 50-year period where nearly the rest of the remaining Jews left Northern Europe. It began with the Rintfleisch massacres. Then in 1306, Philip IV expelled up to 100,000 Jews from France. Finally, in 1348, the Black Death came to Europe. Looking for a scapegoat, Jews were often blamed.

The result was a strong Ashkenazi Jewish culture in Eastern Europe that would linger until the events of the Holocaust.

Golden era in Poland

While life was very hard for Northern/Western European Jews, in Poland, things were comparatively much better. From 1096 to 1348, Poland’s Jewish population became a new middle class in the country. This was codified in 1264 CE when Duke Boleslaw the Pious issued the “Statute of Kalisz”. This statute established a legal foundation for a Jewish presence in Poland. As a result, Jews were subject directly to the King or Duke instead of municipal jurisdictions.[x] This statue was later extended, in the mid-1300s, by King Kazimierz the Great, whom it was rumored had an affair with a Jewish woman named Esther.

Unfortunately, this golden age would not last. In 1367, in the time of our 26th great-grandparents, the first Pogrom in Poland occurred along the German border. It is estimated that as many as 10,000 Jews were slaughtered.[xi] From here until World War II, Poland’s attitude towards it’s Jewish citizens would change many times. It first happened in 1447, when Kasimir IV, the Jagiellon (1447-1492) renewed the rights of Jews in Poland. A mere 7 years later after a military defeat (and pressure from his church), the same Kasimir IV issued the Statue of Nieszawa abolishing the rights of Jews in Poland.[xii]

In 1503, Alexander the Jagiellon reversed position from Kasimir and once again Poland became a haven for Jews in Europe.[xiii] 1525 saw the first Jewish Knight, and 1547 the first Polish Hebrew language printing presses were established. In 1569 Poland and Lithuania united into a commonwealth becoming a major European power. Shortly after, the Va’ad Arba Aratzot was formed. It is otherwise known as the Council of the Four Lands (Greater Poland, Lesser Poland, Lithuania and Mazovia) and was the central body of Jewish self-government. It was the only one of its kind in the history of the Jewish Diaspora.[xiv]

Poland under attack

In 1618, fleeing religious persecution and the impacts of War in Germany, Poland saw its last major influx of Jewish refugees.[xv] At this time, it is estimated that there were over 450,000 Jews in Poland, over half of the 750,000 Jews worldwide.[xvi]

Unfortunately, conditions worsened within the region, when in 1648, the Cossacks staged an uprising in modern-day Ukraine. The resulting pogrom resulted in the death of up to tens of thousands of Jews. The atrocities continued until the Cossacks were defeated by the Polish army. Shortly thereafter, in 1655, Sweden invaded Poland. After Sweden was repelled, pogroms were launched against the Jews who were accused (wrongly) of complicity in this attack.[xvii] [xviii]

As Poland headed into the 18th century it created its own turmoil through political stagnation. This was, in large part, thanks to the “liberum veto” which allowed a single member of the Sejm (Poland’s Parliament) to block the proceedings. Poland became vulnerable to its neighbors, Russia, Austria and Prussia. In 1733, Augustus III succeeded his father, Augustus II. During his reign, 5 of 15 Sejms were dissolved, with the other 10 making no decisions. Midway through his reign, the Seven Year’s War began and Augustus saw Russian and Austrian troops (who were fighting against Prussia and Great Britian) marching through his territory. This would have major consequences for Poland and its Jewish citizens.[xix]

In Part 2 we will explore life in the Lodz region of Poland and meet our earliest known ancestor, Lajzer Olej.

[i] David Biale, “Cultures of the Jews, a New History”, (Schocken Books, New York, 2002), location 10746.

[ii] IBID, Location 10685.

[iii] “The Founding of Israel, The journey to a Jewish Homeland from Abraham to the Holocaust” by Martin Connolly, pg. 42

[iv] IBID

[v] David Biale, “Cultures of the Jews, a New History”, (Schocken Books, New York, 2002), location 10978-11021.

[vi] IBID, location 11196 – 11263.

[vii] JewishGen, “The History of the Jewish Population in Plonsk and the History of the Jews in Poland. Available on-line at: THE HISTORY FROM THE JEWS POPULATION

[viii] Based on the Big-Y DNA test conducted by FTDNA putting Leon Olive into Haplogroup J-FTG13792, which comes from a line of Haplogroups, back to 1000 CE that names their earliest known ancestors in Central Europe, including Poland.

[ix] David Biale, “Cultures of the Jews, a New History”, (Schocken Books, New York, 2002), location 10862-10875.

[x] “1,000 Years of Jewish Life in Polan a Timeline (Taube Foundation for Jewish Life and Culture), available on-line at: Timeline_1000years.pdf.

[xi] JewishGen, “The History of the Jewish Population in Plonsk and the History of the Jews in Poland. Available on-line at: THE HISTORY FROM THE JEWS POPULATION

[xii] “The Founding of Israel, The journey to a Jewish Homeland from Abraham to the Holocaust” by Martin Connolly, pgs. 46

[xiii] IBID, pg. 60

[xiv] “1,000 Years of Jewish Life in Polan a Timeline (Taube Foundation for Jewish Life and Culture), available on-line at: Timeline_1000years.pdf.

[xv] IBID

[xvi] “The Founding of Israel, The journey to a Jewish Homeland from Abraham to the Holocaust” by Martin Connolly, pgs. 74

[xvii] IBID

[xviii] “1,000 Years of Jewish Life in Polan a Timeline (Taube Foundation for Jewish Life and Culture), available on-line at: Timeline_1000years.pdf.

[xix] History of Poland – The states of the Jagiellonians | Britannica