Early Occupation

Life for Jews in Warsaw and Otwock, immediately became difficult. On the first day of 1940, Emanuel Ringelblum observed that “the mortality among the Jews in Warsaw is dreadful. There are fifty to seventy deaths daily.” Prior to the war, it was 10 per day. All foreign contact had been broken and the Nazis began to press women in Warsaw into forced labor.[i]

In February 1940 Jews in Warsaw began to hear rumors about the Łódź Ghetto. In May their fate began to become clear when construction began on walls on Nowy Swiat St. in Warsaw. Despite their fear, and to keep spirits up, the following joke was spread among the Warsaw Jews: “Horowitz [Hitler] comes to the other World. Sees Jesus in Paradise.[sic] ‘Hey, what’s a Jew doing without an arm band?’ “Let him be,” answers Saint Peter. “He’s the boss’s son.”[ii]

For Jews, food was scarce. In Warsaw bread rations for Jews was 200 grams compared to 570 for Christians. The lack of food began to weaken the population in those cities. The Nazis, however, were not sympathetic and reportedly would shoot Jews if they were unable to work or fell sick.

Those in Otwock faced similar conditions where the Nazis began to forcibly cut the beards off of Jewish men. Houses were looted and synagogues were burned down. Forced labor began immediately and was administered by the Judenrat, a Nazi enforced Jewish council to administrate the ghetto.[iii]

The murder of Shraga “Fajwel” Besser

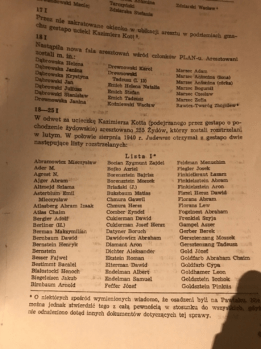

In January 1940, the Gestapo broke up the Polish People’s Indepenence Action organization. Many members were arrested and executed, but their leader, Kazimierz Kott escaped. In retaliation, 255 Jews were arrested, among them was Shraga “Fajwel” Besser. It is likely that they were housed in Pawiak Prison until February when they were shipped to the Palmiry Forest. There they would have lined up in front of a ditch and shot. Fajwel was one of over 1700 executions by the Nazis in that forest.[iv]

Establishing the Ghettos

In September of 1940, in Otwock a decree was published stating which streets the Jews were allowed live. In Warsaw, the ghetto was the subject of many rumors, including that it would be set up in the Pawia Street Prison.[v]

The 12th of October was a “dreadful” day. The residents of Warsaw heard on the loudspeaker that the city was divided into three parts, a German quarter, a Polish quarter and a Jewish Quarter (the Ghetto). 140,000 Jews were forced to leave all of their possessions and move into the Ghetto.[vi] In November the Nazis closed the Ghetto imprisoning the Jews.[vii]

In Otwock there were two ghettos, a “sick” ghetto located in what was a health resort. The other was a residential ghetto. It was an open ghetto which made smuggling goods much easier. This relative freedom would not last and in January 1941, the Ghetto was fenced in. Jews were forbidden to leave without permission.[viii] [ix]

There are not many records about the exact fate of our relatives. Therefore, we must make some assumptions. At the time of the Nazi invasion of Poland, Rachel, widowed wife to Shlomo Yitzhak Popaver was living in Otwock. Her daughter, Naomi who was married to Pinchas Felner and their two children Shlomo and Fela were believed to be living in Otwock,[x] as was her brother Avraham Popaver and his wife (name unknown)[xi] There is little clarity about Rachel’s other children and their family, Isaac (plus his son Shlomo) and Rosa. It is possible that they predeceased the invasion or were living outside of the Warsaw area. The presumption is that they entered either the Warsaw or Otwock Ghetto and were murdered during the Holocaust.

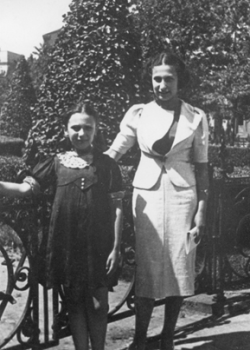

Kalman Besser and Freyda Popaver lived in Warsaw. Fortunately, many of their children made it out of Poland. However, their daughter, Sonia, married Yitzhak Ziskind and had two children, Rena and Abram. It is presumed that they were forced into the Warsaw Ghetto. Kalman and Freyda likely also were forced into the Ghetto with their youngest daughter Rose. None survived.

Little is known about Kalman Besser’s siblings Freyda, Leya, Giteal, Isaac and Shayona. It is presumed that they too ended up and were murdered in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Thanks to the detailed journal by Emanuel Ringleblum, we have some sense of what our relatives who were in the Warsaw Ghetto experienced. In March, after a tough winter, those within the Ghetto began to die at a more rapid rate, causing the need for mass graves. Many were dying from hunger.

Conditions were even worse at the work camps, so Jews in the Ghetto began to hide to avoid being found and pressed into labor.[xii] Therefore, starting on the 19th of April, the Jewish Council, with the help of the Jewish police began the practice of kidnapping inhabitants of the Ghetto. The use of Jews to collect Jews had the desired effect of turning the captives against each other. In one horrible scene a three-year old child tearfully asked a policeman not to take his father away, asking “who will give us bread?”[xiii]

Passover provided a brief respite with some being able to have a Seder with meat, dough balls and wine.[xiv] Sadly, the positive feelings did not last when in May they heard rumors of the Allied defeat in the Balkans and North Africa. They, incorrectly, heard rumors that the German Army was closing in on Palestine.[xv] This must have caused special pain for those like Kalman and Freyda who prayed that their children who now lived there would be safe.

Sanitation was very poor and, therefore, lice became a major problem due to lack of soap. Tuberculosis also spread increasing the already high mortality rate within the Ghettos.[xvi] Programs to disinfect were so ineffective (and costly) that Jews would do what they could to avoid them.[xvii] In September the small ghetto in Warsaw was being liquidated. This reduced the ability to smuggle in much needed food and supplies as it bordered the Christian section. At the same time the inhabitants heard a rumor that the German army had encircled Moscow. This caused despair and made them wonder “from whence shall our help come.”[xviii]

The winter of 1941 was especially bad with frosts appearing in mid-November. Clothing had become scarce and reports of children standing dumbly in the streets weeping from cold were reported. Desperation led to Jews sneaking out of the Ghetto, most were shot.[xix] Those that left with permission often did not fare better as many Jews were, incorrectly, accused of having false passes. Most of them were sent to Auschwitz and murdered.[xx] Unfortunately, and unimaginably, things were about to get worse.

[i] Emmanuel Ringelblum, “The Journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum,” translated and edited by Jacob Sloan, (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015), Kindle edition, pg. 39 – 44 of 421.

[ii] IBID, pgs. 46, 49, 73 of 421.

[iii] Project Muse, the United States Holocaust Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, “Otwock” by Sylwia Szymanska-Smolkin, available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/document/2595/.

[iv] Figure 68, From the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, picture taken by Kaitlyn Logan. Reads: in retaliation for the escape of Kazimierz Kott (suspected by the Gestapo of being of Jewish origin), 255 Jews were arrested and shot in February. In mid-August 1940, the Judenrat received the following two lists of those shot from the Gestapo: list of names: (at bottom) *Some of them are known to have been imprisoned in Pawiak. However, this cannot be stated with certainty in relation to all, since no other documents relating to this case have been found so far.

[v] Emmanuel Ringelblum, “The Journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum,” translated and edited by Jacob Sloan, (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015), Kindle edition, pg. 86 – 90 of 421.

[vi] IBID, pgs. 91, 104 – 106

[vii] IBID, pgs. 119-124.

[viii] IBID

[ix] Project Muse, the United States Holocaust Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, “Otwock” by Sylwia Szymanska-Smolkin, available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/document/2595/.

[x] Yad Vashem, the world holocaust remembrance center, Nomi Felner, (Popaver), Source: Page of testimony, provided by Yekhiel Beser, her nephew, available online: https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/names/411886.

[xi] Yad Vashem, the world holocaust remembrance center, Avram Hersz Popaver, Source: Page of testimony, provided by Yekhiel Beser, her nephew, available online: https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/names/1036482.

[xii] Emmanuel Ringelblum, “The Journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum,” translated and edited by Jacob Sloan, (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015), Kindle edition, pg. 170 – 179 of 421.

[xiii] IBID pgs. 192-200 of 421.

[xiv] IBID pgs. 170-179 of 421.

[xv] IBID Pgs. 211 – 214 of 421.

[xvi] IBID Pgs. 214 – 217 of 421.

[xvii] IBID, Pg. 233 of 421.

[xviii] IBID, Pgs. 256, 257 of 421.

[xix] IBID, Pg 274 of 421.

[xx] IBID, Pg. 254 of 421.